Cone Snail Shell The cone snail shell is the distinctive, cone-shaped shell of marine gastropods belonging to the family CONIDAE. These shells are known for their beautiful patterns, vibrant colors, and, in some species, potent venom.

Characteristics of Cone Snail Shells

- Shape – Conical, with a narrow, elongated spire and a wide body whorl.

- Surface Texture – Smooth and glossy, often with intricate patterns.

- Coloration – Highly variable, ranging from white and brown to vivid orange, pink, or purple, often with bands or spots.

Notable Species & Their Shells

- Geography Cone (Conus geo graph us) – One of the most venomous; its shell has a marbled pattern.

- Textile Cone (Conus textile) – Highly toxic, with a striking geometric design.

- Glory-of-the-Seas Cone (Conus GLO ria mar is) – Once extremely rare, prized by collectors for its intricate net-like pattern.

- Marble Cone (Conus mar more us) – Known for its black-and-white marbled appearance.

Dangers & Uses

- Venom – Some cone snails (especially fish-hunting species) have harpoon-like teeth that deliver potent neurotoxins (conotoxins), which can be fatal to humans.

- Collect ability – Due to their beauty, cone shells are highly sought after by collectors.

- Medical Research – Cone snail venom is

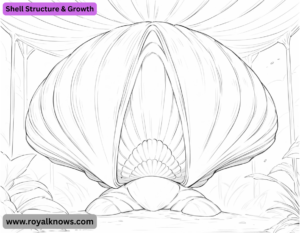

Shell Structure & Growth

- Cone snail shells are calcium carbonate structures secreted by the mantle tissue. Key features include:

- Spire – The pointed top, consisting of older, smaller whorls.

- Body Whorl – The largest and final section, housing the snail’s soft body.

- Aperture – The elongated opening where the snail extends its siphon and proboscis.

- Suture – The seam where whorls join.

- Periostracum – A thin organic layer covering some species’ shells.

- Growth: The shell enlarges as the snail grows, adding new layers at the aperture. Some species have trapdoor-like opercula in juveniles, which they lose as adults.

2. Shell Patterns & Camouflage

- Cone snails exhibit incredible color polymorphism (even within the same species). Patterns serve multiple purposes:

- Camouflage – Blending into coral rubble or sand (e.g., Conus bet ULIN us mimics sand textures).

- Warning Signals – Bright colors (e.g., Conus textile) may signal toxicity.

- Species Recognition – Distinct markings help identify mates.

Notable Patterns

- Net-like designs (Conus GLO ria mar is)

- Spotted or banded (Conus le OPARD us)

- Marbled swirls (Conus mar more us)

3. Ecological Role & Hunting Adaptations

- Cone snails are predators, and their shells reflect their hunting strategies:

- Fish Hunters (e.g., Conus geo graph us) – Lightweight, smooth shells for rapid strikes.

- Moll us c Hunters (e.g., Conus mar more us) – Thicker shells to withstand prey resistance.

- Worm Hunters (e.g., Conus imperial is) – Narrow apertures for probing burrows.

- Venom Delivery: A harpoon-like radula tooth shoots from the proboscis, injecting venom that paralyzes prey.

4. Human Uses & Risks

A. Collecting & Trade

- Historically, rare shells like Conus GLO ria mar is were “prize shells” sold for high prices.

- Overharvesting threatens some species (e.g., Conus CEDONULI).

- Artificial dyes are sometimes used to enhance shell colors fraudulently.

B. Medical Research

- Conotoxins are studied for:

- Pain relief (e.g., PRIALT®, derived from Conus magus).

- Neurological drugs (for epilepsy, Alzheimer’s).

C. Dangers

- Deadly species (Conus geo graph us, Conus textile) can kill humans with their venom.

- Symptoms: pain, paralysis, respiratory failure.

- No antivenom exists—treatment is supportive.

5. Fossil Record & Evolution

- Fossil shells show similar shapes but often lack intricate patterns due to mineralization.

6. Conservation Status

- IUCN Status: Some species are threatened by habitat loss and overcollection.

- CITES: A few (e.g., Conus GLO ria mar is) are regulated in trade.

Fun Facts

- The smallest cone snail (Conus PYMAE us) is under 1 cm, while the largest (Conus aulic us) exceeds 20 cm.

- “Living fossils” like Conus pen NACE us have barely changed in millions of years.

- Some cone snails bury themselves in sand, leaving only their siphon exposed.

Shell Structure & Growth

- Cone snail shells aren’t just pretty—they’re nanotech marvels.

- Crossed-lamellar layers: Calcium carbonate crystals arranged in a crisscross pattern, making shells strong yet lightweight (studied for bio-inspired materials).

- Protein matrix: Organic molecules guide shell growth, influencing color/pattern (e.g., Conus textile’s zigzags are genetically programmed).

- Self-repair: Minor cracks can be sealed with nacre (mother-of-pearl) in some species.

- Fun fact: The shell’s interior (under UV light) sometimes reveals hidden fluorescent patterns invisible in daylight.

8. Biogeography: Where Do They Live

- Hotspots: Coral Triangle (Indonesia/Philippines), Caribbean, East Africa.

- Depth range: Mostly shallow reefs, but some (e.g., Conus pro FUNDOR um) live 1,000+ meters deep.

- al reef complexity

- Ancient Tethys Sea speciation

- Prey diversity driving evolution

9. The Enigma of Cone Shell Chirality

- Most cone shells coil right-handedly (dextral), but rare left-handed (SINISTRAL) specimens exist (e.g., Conus ben GA lens is).

- Caused by mutations in developmental genes—some sell for thousands as collector’s items.

10. Fossil Cones & Evolutionary Secrets

- Oldest known: Conus SAURIDENS (Eocene, 50 MYA).

- Stasis: Some species’ shells haven’t changed in 20 million years—why?

- Possible answer: Their venom is so lethal, shell evolution stalled.

11. The Shell’s Role in Mating & Communication

- Cone Snail Shell Chemical cues: Shells absorb/emit pheromones—some species “smell” potential mates.

- Acoustics: Recent studies suggest certain cones use shell vibrations to deter rivals.

- Gender clues: Females of Conus livid us have thicker shells (possibly for egg protection).

12. Extreme Adaptations

- Deep-sea cones: Transparent shells (e.g., Conus GAUGUINI) to avoid detection.

- Estuary dwellers: Conus TISII survives in brackish water—its shell resists erosion.

- “Zombie” cones: Parasitic barnacles (End o con cha) infest shells, altering their shape.

13. The Dark Side of Shell Trade

- Illegal smuggling: Rare cones (Conus GLO ria mar is) are trafficked on the dark web.

- Fake “gem” shells: Some are coated with resin to mimic gem-quality luster.

- Ethical collecting: Best practices include:

- Never taking live snails

- Avoiding protected species

- Reporting unknown finds to science

14. DIY Science: How to Study a Cone Shell

- Pattern analysis: Use AI tools like i Naturalist to ID species from photos.

- Micro-CT scanning: Reveals internal structure without damage.

- Citizen projects: e.g., “Cone Snails of the Maldives” tracks biodiversity.

15. Unsolved Mysteries

- Why do some cones (e.g., Conus BULLAT us) have inflated “bubble” shells?

- How does Conus geo graph us aim its left-handed so accurately?

- What causes “melanistic” black shells in normally colorful species?

Hyper-Predatory Adaptations The Cone Shell as a Weapon

- Cone Snail Shell The cone snail’s shell isn’t just armor—it’s a hunting platform.

- Hydrodynamic Shape: The streamlined shell allows rapid burrowing in sand to ambush prey.

- Siphon Notch: A small groove in the shell’s aperture directs water flow, enhancing chemical detection of prey.

- Harpoon Storage: The proboscis (venomous harpoon) retracts into the shell’s rostrum when not in use.

- Ultra-Rare Behavior: Some Conus geo graph us individuals “net hunt”—expanding their rostrum like a web to engulf fish!

17. Shell Chemistry: Nature’s pH Regulator

- Cone snails manipulate their shell’s biomineralization in extreme environments:

- Deep-Sea Acid Resistance: Hydrothermal vent species (Conus FERRUGINOS us) incorporate magnesium calcite to resist dissolving in acidic water.

- Metal Scavengers: Shells of polluted-region cones (Conus ERMINEUS) can contain traces of lead & mercury—potential bioindicators.

- Lab Breakthrough: Scientists are mimicking cone shell growth to create self-healing ceramics.

Get article on pdf file….Click now

……….Cone Snail Shell………..