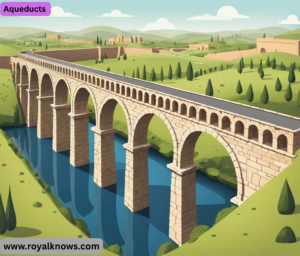

Aqueducts An aqueduct is a man-made channel or pipeline designed to transport water from a distant source to a desired location, typically a city, town, or agricultural area. While most people picture the massive, graceful stone arches (which are actually just a small part of the system), an aqueduct is the entire water conveyance system. This system often included:

- Source: A spring, river, or lake.

- Tunnels: Bored through mountains and hills for a direct route.

- Arcades (the famous arches): Used to carry the channel at the necessary height across low-lying terrain like valleys and plains.

- Sedimentation Tanks: To help filter and settle out impurities.

Early Aqueducts:

- The earliest civilizations, like the Assyrians, Egyptians, and Indians, built sophisticated irrigation canals.

- The most famous early aqueducts were built by the Romans, who perfected the technology on a massive scale to support their growing urban populations.

Roman Aqueducts:

- The Romans were master hydraulic engineers. Their first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was built in 312 BC. By the peak of the Roman Empire, the city of Rome was supplied by eleven major aqueducts providing over 1 million cubic meters of water per day (enough for over a million people).

Key Features of Roman Aqueducts:

- Gravity-Powered: The entire system relied on a constant, gentle downward slope (as little as 1 foot per mile) from the source to the city. This required incredible precision in surveying.

- Durability: Built from stone, brick, and a special waterproof concrete called opus caementicium.

- Maintenance: Access shafts were built along underground sections for inspection and cleaning.

- Legacy: Roman aqueducts were so well-built that some, like the Aqua Virgo in Rome (now the Trevi Fountain’s source) and the Pont du Gard in France, are still standing or even partially operational today.

Post-Roman Era:

- After the fall of Rome, large-scale aqueduct building ceased in Europe for centuries. Knowledge was preserved and advanced in the Islamic world, where sophisticated water management systems, including qanats (gently sloping underground tunnels), were developed.

Modern Aqueducts:

- The need for large-scale water transport returned during the Industrial Revolution. Modern aqueducts are essential for supplying massive metropolitan areas and are feats of engineering, though they use different materials like steel, concrete, and pressurized pipes instead of gravity-fed open channels.

Famous modern examples include:

- The California State Water Project: A vast network of canals and pipelines moving water from Northern California to the drier south.

- The Central Arizona Project: A 336-mile canal that carries water from the Colorado River to central and southern Arizona.

Why Were They So Important?

- Public Health and Sanitation: They provided a reliable source of clean water, reducing dependence on often-contaminated local wells and rivers. This helped reduce the spread of waterborne diseases.

- Urban Growth: A guaranteed water supply allowed cities to grow far beyond what their local water sources could naturally support.

- Public Amenities: Water was supplied to public fountains (for the poor to collect water), public baths (a central part of Roman social life), and latrines.

- Agriculture: Water was used for irrigation to increase crop yields and support larger populations.

- Industry: Powered mills, supplied water for mining operations, tanning hides, and other industries.

Famous Examples

- Pont du Gard (Nîmes, France): Perhaps the most famous Roman aqueduct bridge due to its stunning preservation and height (160 ft / 49 m). It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Its two tiers of arches dominate the city center and it was used well into the 20th century.

- Valens Aqueduct (Istanbul, Turkey): Built in the 4th century AD, a large section of its arcade still stands prominently in the heart of modern Istanbul.

- California Aqueduct (USA): The backbone of the State Water Project, it is the longest aqueduct system in the world at over 700 miles (1,100 km).

The Nuts and Bolts: How Did They Actually Work?

- The genius of the Roman aqueduct system wasn’t just the arches; it was the meticulous planning and execution.

The Survey (Agrimensores):

Before a single stone was laid, Roman surveyors (agrimensores) performed an incredible feat of engineering. Using tools like the:

- Groma: For aligning straight lines and right angles.

- Chorobates: A long, precise leveling tool filled with water.

- They mapped a continuous, gentle downward slope from the water source, often dozens of miles away, to the destination city. This gradient could be as slight as 1:5000 (a 1-meter drop for every 5 km).

The Route: More Tunnel Than Archade

- A common misconception is that Roman aqueducts were mostly above-ground arches. In reality, to maintain the crucial gradient and avoid long detours, approximately 80% of Rome’s aqueduct systems ran underground.

- Subterranean Channels: These were dug into hillsides, lined with stone and waterproof cement (opus signinum), and covered. This protected the water from evaporation, contamination, and enemy attack.

- Tunnels: Mountains were tunneled through. Work started from multiple vertical access shafts (putei) dug along the proposed route, which also later served for maintenance.

Crossing Valleys: The Arcades and Siphons

When the aqueduct encountered a valley, engineers had two main solutions:

- Arcades (The famous arches): These were not the first choice due to the immense cost and labor. They were used when the valley was too wide or deep for a siphon. The arcades were built with a continued gentle slope, meaning they often started low on one side and rose to their greatest height in the middle of the valley.

- Inverted Siphons: More common than often thought, especially in the Greek world and later Roman provinces. Water was fed into lead or ceramic pipes that ran down one side of the valley, across the bottom, and up the other side. The pressure from the weight of the water coming down forced it up the other side, though not to its original height. This required incredibly strong, pressure-resistant pipes.

Maintenance and Regulation:

Aqueducts were not “build it and forget it” projects. They required constant care.

- Curator Aquarum: A high-ranking official, like the famous Frontinus (who wrote a detailed book on Rome’s water supply), was in charge.

- Teams of Workers: Slaves and later state-employed crews (aquarii) constantly patrolled the channels, cleaning out mineral deposits (like calcium carbonate, which built up over time), repairing cracks, and removing debris.

- Control at the Castella: The distribution tanks (castella divisoria) were where the water was allocated. Frontinus complained about unscrupulous users bribing workers to insert illegal pipes into the channel to steal water before it reached the official distribution point.

Social and Cultural Impact: More Than Just Water

The aqueduct was a powerful symbol and a practical tool that shaped daily Roman life.

- A Symbol of Civilization: The abundance of flowing water was a clear marker of Roman sophistication and power. It distinguished a Roman city from a “barbarian” village.

- The Baths (Thermae): Aqueducts made the massive Roman public baths possible. These were not just for cleaning but were complex social centers with libraries, gyms, and gardens. Access to baths was cheap or free, making them a key part of the Roman “bread and circuses” social policy.

- The End of the Aqueduct: When aqueducts were cut by invaders or fell into disrepair after the fall of Rome, it had a catastrophic effect. Without a clean water supply, urban populations plummeted. People were forced back to using contaminated local wells and rivers, leading to a rise in disease and a decline in public sanitation that characterized much of the Middle Ages. The inability to maintain these systems was a tangible sign of the loss of Roman engineering knowledge and centralized administration.

Fascinating Facts and Trivia

- Some aqueducts were preferred for drinking (e.g., Aqua Marcia), while others were used for irrigation or filling baths because the water was harder or less tasty.

- The Trevi Fountain’s Source: The famous Trevi Fountain in Rome is the terminal showpiece of the Aqua Virgo, an aqueduct completed in 19 BC by Agrippa. Remarkably, it still functions today, supplying water to the fountain.

- Not Just Romans: While the Romans perfected them, other cultures built impressive aqueducts. The Nazca culture in Peru (circa 500 AD) built underground aqueducts (puquios) to access groundwater in the desert, some of which are still used today.

- The Cost of Failure: Building an aqueduct was a huge financial gamble. If the surveyors miscalculated the gradient, the entire project was a useless, monumentally expensive failure. There are records of aqueducts that simply did not work because the slope was incorrect.

- Animal Inside: The calcium carbonate deposit that built up inside channels over centuries is called sinter. It can be so thick that it drastically reduces the channel’s capacity. Studying the layers of sinter can tell archaeologists about the water chemistry and flow history over centuries.