Discourse particles Discourse particles are words or short phrases that don’t contribute much to the literal meaning of a sentence but play an important role in conveying tone, attitude, or emphasis in spoken or informal written language. They are especially common in many East and Southeast Asian languages but also appear in other languages, including English.

Examples in English:

- “Oh” – Expresses surprise or realization.

- “Oh, I didn’t know that!”

- “Well” – Used for hesitation or transition.

- “Well, I guess we could try.”

- “You know” – Seeks agreement or fills pauses.

- “It’s just, you know, not that easy.”

- “Like” – Used for approximation or filler.

- “It was, like, really weird.”

- “Actually” – Introduces a correction or contrast.

- “Actually, I think you’re wrong.”

- “Right” – Confirms understanding.

- “Right, so we meet at 5?”

Examples in Other Languages:

- Mandarin (Yeah, “ma”, Bar “ba”, ah “a”)

- Japanese (hey “ne”, Yo “yo”,mosquito “ka”)

- It’s okay (Daijōbu yo – “It’s fine, I assure you.”)

- Cantonese (ah “aa”, La “laa”, of “ge”)

- Yes!(Hai aa! – “Yes, indeed!”)

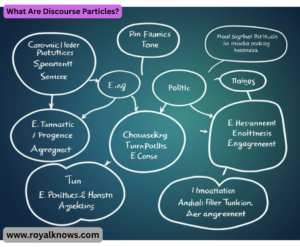

Functions of Discourse Particles:

- Softening or strengthening statements (“just”, “really”)

- Seeking agreement (“right?”, “isn’t it?”)

- Expressing hesitation or doubt (“um”, “well”)

- Conveying mood or attitude (“sigh”, “wow”)

- Managing conversation flow (“so”, “anyway”)

What Are Discourse Particles?

- Discourse particles (also called pragmatic particles, modal particles, or filler words) are short, often unstressed words that:

- Do not change the core meaning of a sentence.

- Add nuance, tone, or emotional context.

- Signal the speaker’s intent (e.g., hesitation, emphasis, politeness).

- Help manage conversation flow (e.g., turn-taking, agreement-seeking).

- They are more common in spoken language but appear in informal writing (e.g., texts, social media).

3. Language-Specific Deep Dives

A. Mandarin Chinese

- Bar (ba) – Softens suggestions or seeks agreement.

- ah (a) – Expresses realization or emotion.

B. Japanese

- Japanese particles (Final particle shūjoshi) are sentence-final and convey attitude:

- mosquito (ka) – Neutral question marker.

- Yo (yo) – Adds emphasis or assurance.

- hey (ne) – Seeks agreement (“isn’t it?”).

- It’s cold. (“It’s cold, right?”)

C. Cantonese

- Cantonese particles are tonal and abundant, often changing meaning based on pitch:

- La (laa1) – Urgency or suggestion.

- Hurry up! (“Hurry up!”)

- of (ge3) – Softens assertions.

- I understand. (“I understand (no worries).”)

- Meow (me1) – Disbelief or sarcasm.

- Really? (“Really? (I doubt it)”)

D. German

- German uses modal particles (Abtönungspartikeln) to adjust tone subtly:

- “doch” – Contradicts a negative assumption.

- “Du hast doch Zeit!” (“You do have time!”)

- “mal” – Softens requests.

- “Komm mal her.” (“Come here [casual].”)

4. Why Are Discourse Particles Important?

- Social cues: They signal politeness, friendliness, or sarcasm.

- Conversational rhythm: Fillers like “um” hold turns in dialogue.

- Cultural nuance: Misusing them can make speech sound unnatural (e.g., overusing “like” in English or skipping hey in Japanese).

5. Common Mistakes Learners Make

- Overusing fillers: “So, like, I was, um, going…” → sounds hesitant.

- Misplacing particles: In Mandarin, ?(ma) only ends yes/no questions.

- Ignoring tone: Cantonese ah (aa4 vs. aa3) changes meaning.

6. Advanced Notes: Theoretical Classification

- Linguists categorize discourse particles by:

- Position: Sentence-final (Mandarin Bar ), medial (English “like”).

- Function: Interactional (“hmm”), attitudinal (“wow”).

- Clitic vs. particle: Some attach to words (e.g., French “tu” in “Manges-tu?”).

7. Research & Further Reading

- Mandarin: Li & Thompson’s Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar.

- Japanese: Onodera’s Japanese Discourse Particles.

- Cross-linguistic: Schiffrin’s Discourse Markers.

Discourse Particles in Understudied Languages

A. Korean (particle eojosa)

- Korean particles often reflect hierarchy and politeness:

- -yes (ne) – Mild surprise or realization.It’s raining!(“Oh, it’s raining!”)

- -Yeah (janha) – Frustrated emphasis (“You know this!”).

- It’s a work test! (“The exam is tomorrow, duh!”)

- -Thera (deora) – Retrospective recollection.

- That place was really beautiful. (“That place was truly beautiful, I tell you.”)

B. Thai (help khám chûay)

- Thai particles are tonal and gender-sensitive:

- Yes (ná) – Softens requests (neutral).

- Help me please (“Please help me.”)

- Wa (wá) – Masculine bluntness (informal).

- ไLet’s go! (“Let’s go, man!”)

- yes (jâ) – Feminine gentleness.

- Very much. (“So pretty, dear.”)

C. Arabic (letters of meaning huruf al-ma’na)

- Dialectal particles reveal regional identity:

- Or (yā) – Vocative or emphasis (pan-Arabic).

- Oh God! (“Oh God!”)

- Bus (bas) – “Enough” (Levantine) → Can dismiss topics.

- That’s it! (“Enough, stop!”)

- Even if (wākha) – “Even if” (Moroccan Darija).

- Even if it is expensive (“Even if it’s expensive.”)

2. Computational Linguistics & AI

- Speech recognition: Fillers like “um” are now tagged in datasets (e.g., Switchboard Corpus) to train AI.

- Machine translation: Particles are often dropped in translations (e.g., Japanese Yo → English “!”), losing nuance.

- Sentiment analysis: Particles like “just” can flip tone:

- “Just stop.” (annoyed) vs. “Just wondering.” (polite).

3. Historical Linguistics: How Particles Emerge

- Grammaticalization: Lexical words → particles.

- Mandarin It’s (le) evolved from a verb meaning “to finish” → perfective aspect marker.

- English “like” shifted from preposition (“like a bird”) → quotative (“She’s like, ‘No way!'”).

- Borrowing: Cantonese La (laa) comes from Portuguese “lá” (there).

4. Sign Languages: Non-Manual Markers (NMMs)

- In ASL, facial expressions and body movements act as visual discourse particles:

- Raised eyebrows = “Are you serious?” (similar to English “really?”).

- Head tilt + pause = “You know what I mean?” (like Japanese ね).

- Mouth “th” (disapproval) = Equivalent to “meh” or “whatever.”

5. Internet & Gen Z Slang

- Digital communication reinvents particles:

- “Periodt” – Strong emphasis (Black English Vernacular → TikTok).

- “She’s the best, periodt.”

- “Fr” (“For real”) – Seeks confirmation or sincerity.

- “That’s crazy, fr?”

- (skull emoji) – Sarcastic “I’m dead” (replaces “lol”).

6. Endangered Languages & Particles

- Some particles are untranslatable and vanish with language loss:

- “It’s raining, ’á.” (“I heard it’s raining.”)*

- Irish Gaelic “arú”: Expresses sudden realization, like “Oh!” but context-bound.

7. Experimental Linguistics: Brain Processing

- ERP studies show particles like “oh” trigger P600 waves (syntactic surprise).

- Left-hemisphere bias: Most particles are processed as language, but fillers (“um”) activate right hemisphere (social cognition).

8. How to Master Particles Like a Linguist

- Corpus analysis: Search for [particle] in language databases (e.g., COCA for English).

- Pragmatic failure diary: Record when misuse causes confusion (e.g., overusing よ in Japanese → sounding aggressive).

9. Future Directions

- AI chatbots: Can GPT-5 replicate natural particle usage? (Currently struggles with Cantonese frame aa3.)

- Neuroscience: Do bilinguals process particles differently in L1 vs. L2?

Philosophical Linguistics: What Are Particles, Really?

A. Wittgenstein’s “Language Games”

- Particles are “moves” in social interaction, not just words. Example:

- Saying “hmm” in English = Passing the conversational turn non-verbally.

- Japanese I see (sō ka) = Acknowledgment as a social ritual, even if the listener already knew the info.

B. Grice’s Maxims & Implicature

- Particles often flout conversational rules to imply meaning:

- Mandarin Well (ma) softens requests by implying shared knowledge (“You already know this, right?”).

C. Derrida’s “Différance”

- Particles have no fixed meaning—their function emerges from contrast:

- English “like” vs. “um” → Both fill pauses, but “like” also frames approximations.